Nine Common Beginner Climbing and Mountaineering Mistakes To Avoid

Whatever pursuits we turn our hands to in life, as beginners the chances of making mistakes are exceedingly high. Climbing and mountaineering are no exception to this rule, only the potential consequences of our errors in either of these high-risk activities are considerably more severe than in most others. While in some leisure pursuits mistakes are a prerequisite to mastery and can be quickly forgotten once committed. But, on the rock, no such luxury is granted: mistakes here, unfortunately, are most likely to result in some form of injury or even death for you or your climbing partners. Luckily, these mistakes are not inevitable and can be easily avoided with a bit of practice, care and know-how. Below, and in no particular order we take you through nine of the most common beginner mountaineering mistakes.

1. Getting Lost

Sh*t happens. In the high mountains, weather conditions can change quickly and seriously impact visibility and orientation. While route-finding and getting our bearings is usually not too difficult in good weather, when immersed in thick fog or cloud the nature of our climb changes drastically. A hugely-underrated skill often overlooked by newcomers to mountaineering is the use of a map and compass, an ability which just might prove to be lifesaving in such a scenario. Time and practice are required, but navigation skills can be developed gradually and in low-risk situations. To start with, practice on easy terrain without too many notable features and try to find your way around, taking bearings and setting directions of travel. When you venture into the mountains, even in good visibility, take frequent breaks to consult your map and get used to navigating with the aid of a compass.

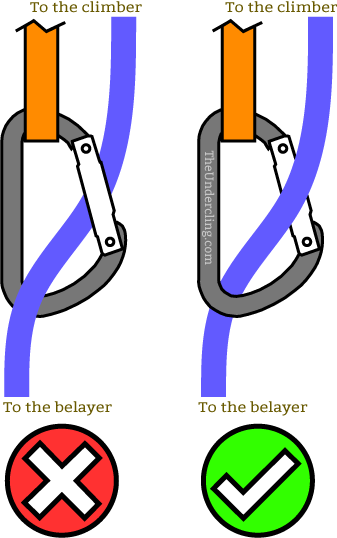

2. Back-clipping

One of the easiest-to-make mistakes for anyone starting out in climbing, is back-clipping. Back-clipping occurs when the rope is incorrectly clipped into the bottom carabiner of the quickdraw so that it runs behind the gate or clip as opposed to in front of it. See photo above.

The danger in doing so is that, in the event of a fall, the rope is liable to unclip itself from the ‘biner and, well, the rest is should we dare say, history? Avoiding this mistake is as simple as forming a mental picture of how a correctly-clipped carabiner should look or carrying a mental-memo or acronym onto the rock with you such as R.B.C (Rock-Biner-Climber) to describe the flow of the rope through the ‘biner from the ground up.

3. Complacency

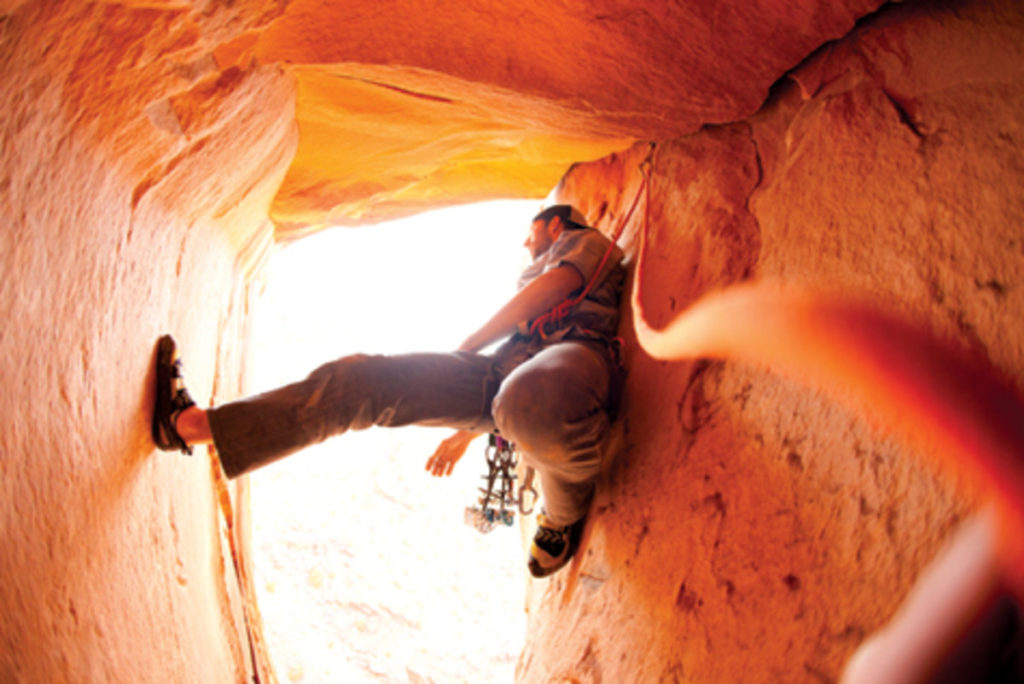

Photo Captured By Andrew Burr

Perhaps the most widespread and dangerous of all climbing mistakes, complacency covers a wide variety of errors ranging from lackadaisical footwork to not screwing up carabiners to not paying attention to our climbing partner while he or she is climbing.

This tendency usually sets in immediately after the beginners stage, when we start to get comfortable – too comfortable – with the ins and outs of rope work etc., and before we have witnessed that first serious accident which usually never allows us to take any aspect of climbing so lightly or for granted again. Avoiding complacency is achieved by simply reminding ourselves of the potential consequences of an overly-casual approach. A quick Google search for ‘climbing injuries’ should do the trick!

4. Over-gripping

As a species blessed with opposable thumbs, dexterous fingers, strong forearms and accustomed to utilising these attributes when wishing to keep something in our grasp, the natural tendency during first ventures on the rock is to grab on and squeeze for dear life. This approach, however, is counterproductive. When squeezing our arm and hand muscles for all they are worth we speed up the build-up of lactic acid, and creator of that nasty burning sensation which is apt to turn our muscles and fingers feeble and uncooperative in no time at all.

The result, in most cases, is being lowered off the climb prematurely. A cure for this progress-hampering tendency is to practice only a few feet from the ground in order to build up trust in our points of contact with the rock, particularly our feet (bouldering gyms and training are excellent ways to learn and/or correct over-gripping). Eventually, we come to see how little force is actually required to stay balanced, thus saving the strength in our forearms, hands and fingers for later in the climb.

5. Benightment

What goes up must come down – preferably in a safe and controlled a manner as possible. Benightment occurs in mountaineering when a touch of summit-fever or over-exuberance carries the climber up stretches of climb he or she will later be unable to descend. Going up, gravity is with us, holding us to the slope and aiding our adherence to holds and steps.

On the descent, the reverse is true – facing down, gravity wants to take us off the slope and the angle is less favorable to grip or adhesion. Down-climbing is far more difficult than up-climbing and it is believed that up to 80% of accidents in the mountains occur on the way down. To avoid this mistake, a simple awareness of our progress, the terrain, and constant assessments of the big picture while ascending should help us avoid going up something we’ll later struggle to descend.

6. Lowering or Abseiling Off the End of the Rope

When belaying, the length of rope required for any given pitch isn’t always known. If we have a 60m rope and are on what turns out to be a 30+m climb, shortly before our partner reaches solid ground safely we are going to run out of rope, leaving him or her to fall if we don’t notice the error in time. To avoid this potentially deadly mistake, make sure to tie a knot in the end of the rope so as to prevent it slipping through the belay device when it runs out. Simple, but essential…

A similar mistake, which some may consider the sole preserve of contenders for the Darwin award but is oh-so-easily done, is abseiling off the end of the rope. Again, a good knot in the ‘dead’ end of our rope will preclude the risk of it slipping through when reaching our belay device.

7. Caught in an Avalanche

Avalanches are a near ever-present hazard in the world of mountaineering. If you are keen on summiting high peaks, the chances are they will have some degree of snowcover year-round. While avalanche risk assessment is not an exact science, there are certain steps we can take to ensure we maximize our chances of avoiding the dangers:

Check the avalanche forecasts for your area. The European Avalanche Warning Service, avalanche.org and the American Avalanche Association cover most mountainous regions worldwide.

Pay attention to the aspect of slope and changes in weather. Avalanches are most likely to occur on 30-45 degree slopes (but can carry momentum over lesser slopes with inclines of as little as 15 degrees) and when there have been significant changes in temperature in the days preceding your climb. If there has been fresh snowfall on an existing snowpack or a sudden thaw, stay clear.

Take a course in avalanche safety. In most mountainous regions, there are normally several outfits offering weekend or intensive day-courses. Finally, consider investing in avalanche safety gear: a snow-shovel (to check the snow pack for weak layers, slab or powder accumulations on top of condensed snow, all of which present serious risk), a probe (to search for other climbers buried in an avalanche), a beacon or transceiver (a device that allows you to be located and also to locate other climbers in the event that you or they are buried following an avalanche) and an Avalanche Airbag (an inflating device that prevents complete burial).

8. Falling Through a Cornice

Cornices are large, often overhanging accumulations of snow on mountain ridges, usually on the leeward side of prevailing winds. To the untrained eye, these protuberances may look solid, safe, and are often indistinguishable from the rest of the snow on a ridge, saddle or mountainside. Many mountaineers – newbies and veterans alike – underestimate the dangers of cornices, or overestimate their staying power, only to have the cornice collapse, taking them with it.

Avoiding this hazard requires awareness of where cornices are likely to be and developing a strategy for dealing with one should you encounter it. The potential ‘fracture zone’ of a cornice is exactly where the tip of the inverted ‘V’ on the ridge is positioned beneath the snow. Anything on or to the leeward side of this is, essentially, the ‘death’ zone. First assess where you assume the point of the ‘V’ to be, then go a few steps lower to provide a buffer.

9. Not Tying In Properly

Whether fixing a belay or preparing to climb, getting your knots right is perhaps the most fundamental responsibility and yet most frequently-cited error among climbing newbies. Two habits can help you avoid this risk. First, practice your knots and tying-in at home until tying into your rope has become as natural as tying your shoelaces. Secondly, always do a buddy-check, no matter how ‘uncool’ it may seem – if would be far less cool for either you or you partner to suffer a serious fall because you hadn’t taken a moment to double-check each other’s knots.

As you can see, the potential to make mistakes while climbing and mountaineering are numerous and varied. Understanding the risks, common mistakes and skills required are essential for any newbie, veteran alike and will leave you to enjoy many safe, happy days in the mountains or on the crags for a long time to come.

No Comment